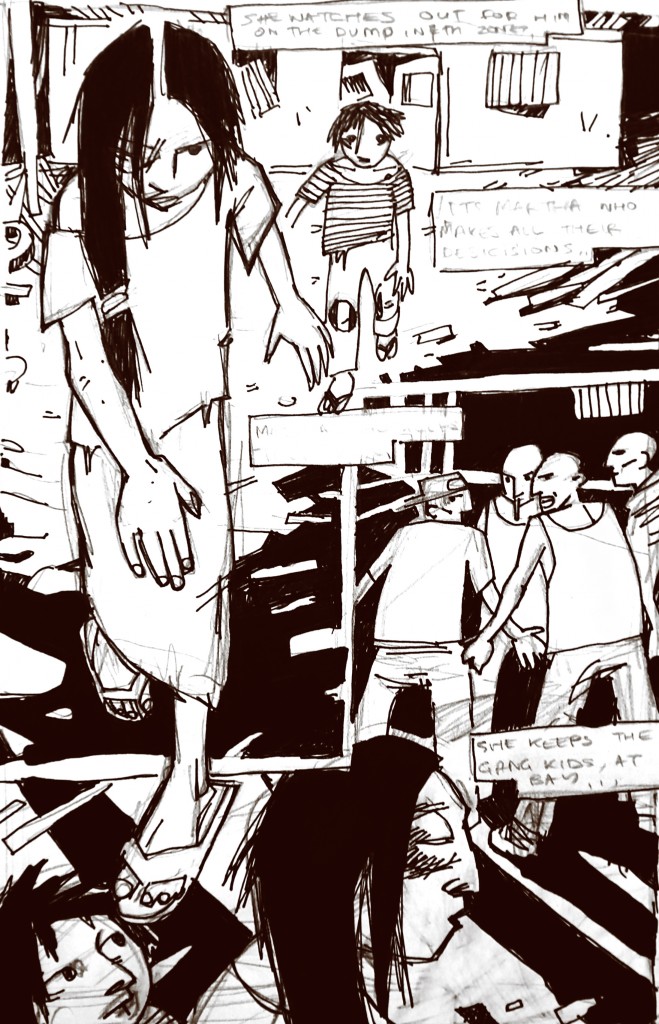

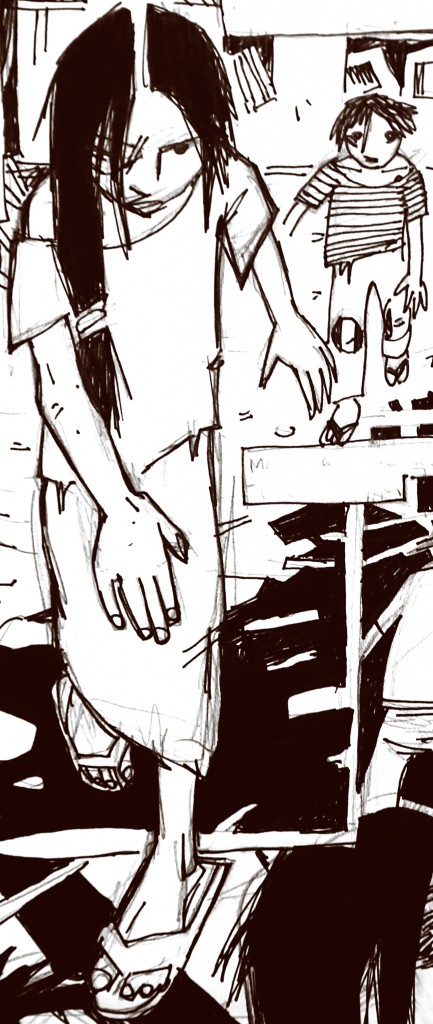

Story by Si Mitchell. Illustrations by the super-talented Jake Pond.

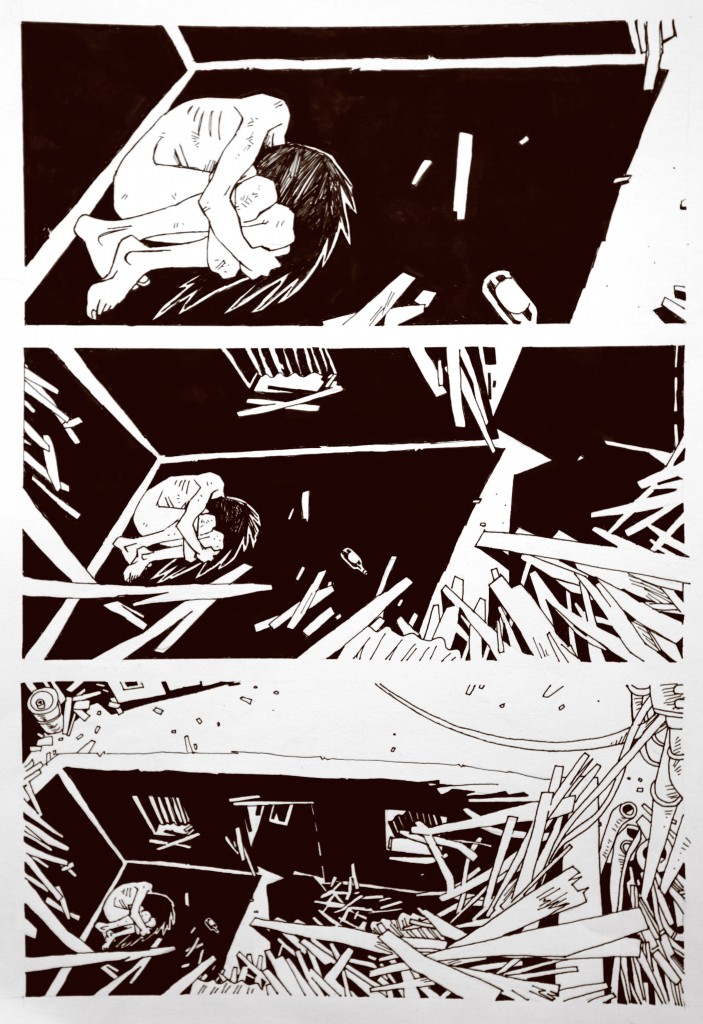

Pablo does not move until he can no longer smell the tobacco and beer. He knows silence in the city doesn’t mean safety, just that the current dangers are still unknown.

Marta is not moving. Pablo takes the remnant of plastic sheeting that came between him and a similar fate and drapes it over her stained and half naked body. She lies awkwardly, half on and half off the old tabletop they pinned her to. It rocks gently on a chunk of concrete, one of many strewn across the floor of the building they’ve been calling home these last weeks. That’ll stop now too. Marta’s body lies creased – twisted like one of the bar-ribbed dead dogs they find on the dump. Pablo is surprised by how little there is to her. He shouldn’t see her like this. He tries to look away as he tucks the plastic around her. He tries to be gentle but can’t mask the clumsiness that comes with being seven years old and scared out of his wits.

But Marta doesn’t stir. What little city light has leeched in through the tears in the back wall bounce blue green off her shiny, crow feather hair. The band she likes to hold it back with is gone and black tails hang across her face hiding her eyes. Pablo cannot see if they are open or closed. His breathing quickens. He wants to see her eyes sparkle like he knows they can in the dark. He wants to hear her do her raucous, shameless laugh. At nine years old Marta may only be two years older than Pablo, but she is all that stands between him and what’s outside. If Marta dies he has no idea how he’d survive. He should have done something. But what? Died too?

Done aside, Pablo has no idea what to do. Embarrassed by his lack of bruises, he shuffles back to where the shadows are denser. Without Marta to check them, Pablo’s demons are loose. But darkness owes no loyalties and hides small boys just as well as bogeymen.

He returns to his hiding place under the splintered desk with its drawers pulled out. The wall against his back is a certainty, as is the dislodged brick he perches on, skinny arms wrapped round skinny knees. Pablo’s street-black toes grip the brick’s coarse edges, and he rocks back and forth like one of the wing-clipped birds the old ladies sell in the covered market. And though he doesn’t dwell on it, right now Pablo understands exactly why they swing the way they do.

Headlights skitter up the walls and across the remaining rafters of the tiny warehouse as cars lurch along the rutted road outside. The roof they once held up is now scattered across the floor providing, amongst other things, the see-saw for Marta’s tabletop. Every now and again the lights provide Pablo with a snapshot of Marta’s small round face, but it remains unchanged. And any relief brought by the light is tempered by the fear the car may stop.

Marta is all the family Pablo has in the city. She has looked out for and after him – on the dump, in the zones. She keeps the bandas – the gang kids – and the drogueras – the druggies – at bay. She sees that he eats. She found them the collapsing shack in barrio La Libertad where they sheltered during the rains until it washed away. She’s just a child, but she’s been like a mother to him since he came to the city. Since he left the mountains. Since he left his own mother.

Pablo isn’t entirely sure why he had to leave Quiche province, but he distinctly remembers his uncle Moses bringing him on the bus from the village to the city. His mother and father had had many children and Pablo, as the oldest, had to leave to find work. Yes, that was why – to earn money so that one day he could return to them a rich man.

His father had worked his small patch of land hard. Pablo had helped him plant maize, lift weeds and pick beans from the few coffee plants that nestled beneath the single tall avocado tree. He remembers how the sun lashed their backs as they worked and how they would rest under those big green leaves and share water from his father’s stoppered bottle. His father’s name was… What was it? Julian, that’s it, a silent sinewy jackal with soil dark skin. He wore ancient colourless plastic sandals and trousers that ended at his calves. A straw hat kept the sun from his beady black eyes. Pablo cannot picture how he looked without it. His mother, she had tended the house and the children. Seven, maybe eight of them? Girls. Any boys? Nine kids including Pablo – the oldest, the bravest… yes, the only boy, the one who had had to leave. The one who will, one day, return. They called her… what was it? Was it Marta?

Pablo pictures his mother – strong, but not big, wiry, strict but loving. And like all the women that gather at the firepit she wears the huiple of the Quiche Indian, bright pink and yellow and thick stitched with too-green trees and sticky campesinos labouring under rainbows. Pablo remembers the giant coloured handles that would connect the hills above his village. Nunca ay arco iris en la ciudad. There’s no rainbows in the city.

Why did an only son leave his family? Why did his mother let him go? He can picture her kneeling outside that tough little house, a fat band of threads rising from her waist to the eaves while her fingers whittle among them spinning magical patterns in elaborate pieces of cloth. His sisters sit behind her, miniaturised versions of the same, a weaving train with rattling back-and-fore engines that never leaves the station.

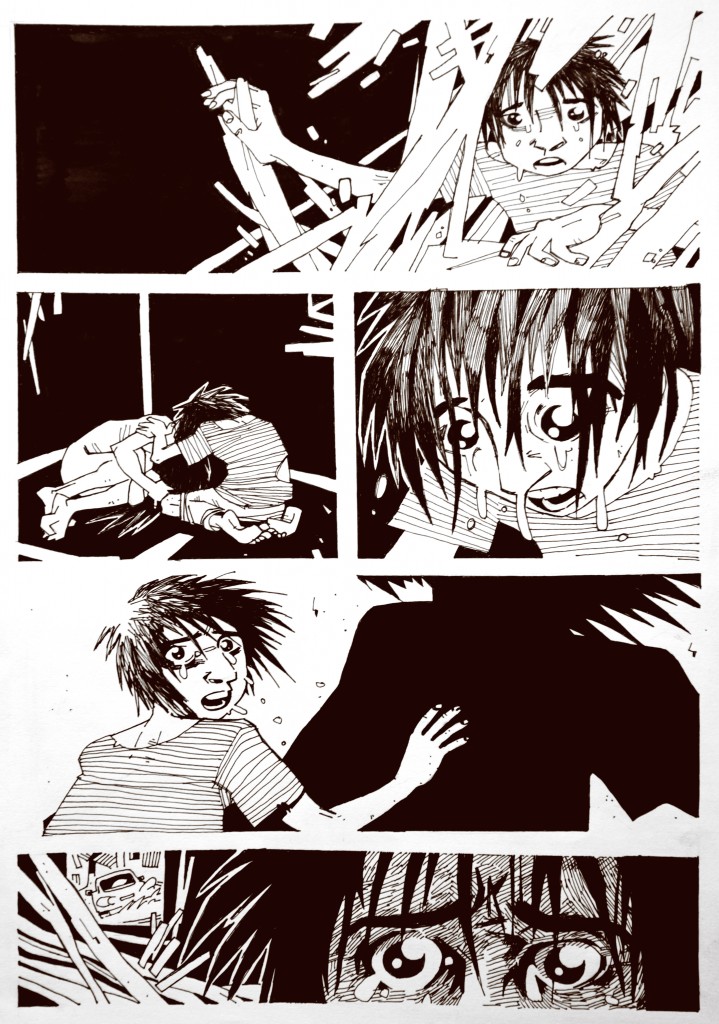

Pablo doesn’t remember falling asleep, but the first thing he hears when he wakes is Marta’s breathing. Slow and steady. Alive. Awake. If she’s moved, Pablo can’t tell. She stares straight ahead, and does not turn her face to acknowledge him as he crawls over to her. The door she lies across lifts and falls, almost imperceptibly, as she breathes.

“Marta?”

She is the one with the blood dried on her mouth and the bruises beginning to cloud her face, but somehow the dynamic between them is the same. Pablo needs reassurance. Marta must give it.

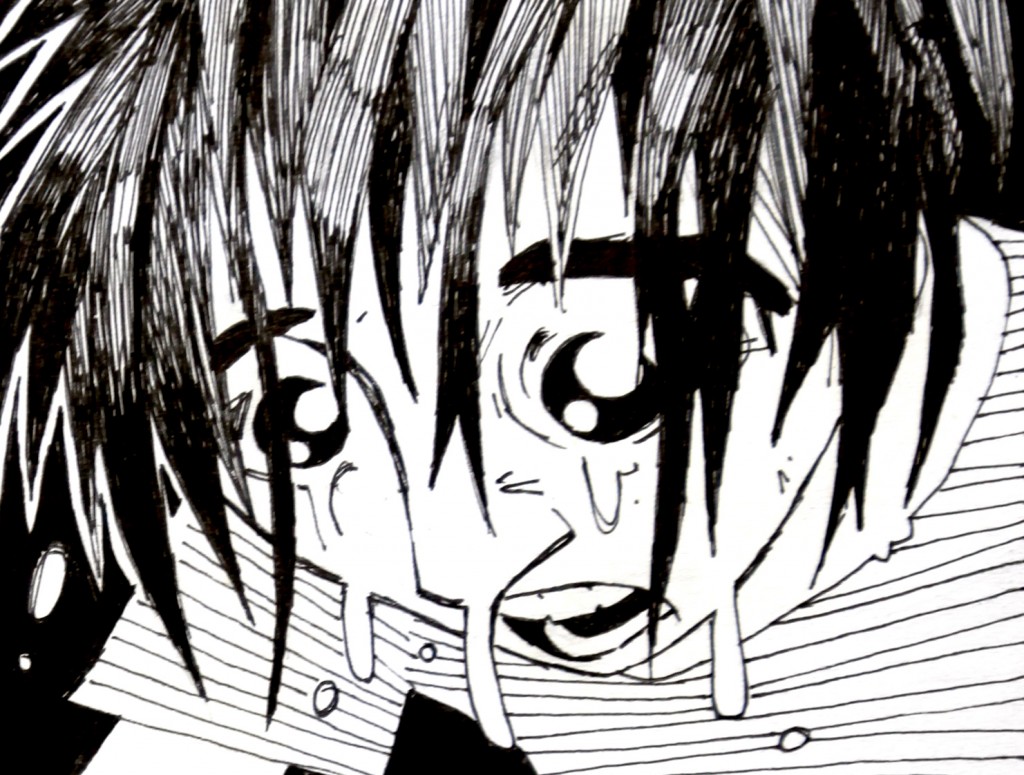

But her face is blank, motionless, save a slim trickle connecting one eye to the tabletop. It’s Marta’s job to have the answers. Pablo has never had to consider a limit to her strength before. Bubbles form and pop on his flickering lips.

He reaches out a hand to wipe away her scary tears but misses and jabs Marta hard on the side of her nose. She doesn’t recoil, but the knock makes her look at him.

She studies Pablo for several seconds, before realising that he’s waiting for, needing instructions.

Without moving she says: “Let’s go out of here.”

Pablo sags, relieved to give up his decision making duties. Not that he had made many, any, in the short time he had had them.

He looks away while Marta dresses herself – just as he had looked away last night – and they climb across the debris of brick and tile and out through the splintered door the cops kicked in and into the street.

Cartons and cans and bags and straws and paper cups blanket the city. Legs and breasts and faces slashed by smiles and kitchen knives grin up at the children from flapping newspapers. And though it didn’t rain in the night, the mesh of ruts and potholes that form the barrio’s streets are, as ever beneath this detritus, ankle deep in filthy brown soup.

Marta walks, oblivious to the sunlight or the sounds, or whether or not her feet fall in or out of water, while Pablo skips in attempted step behind her.

The EJE1 is a screeching, smoking brawl of cars, trucks and buses from all points north that butchers its way into the city each morning and out again at nightfall. Guate – as the residents know their city – is a passable venue to turn a coin, but it’s no place to spend the night if you can afford not to.

Marta doesn’t even check her step as she glides into the pandemonium. Pablo pursues her into the traffic but the wail of shoeless-brakes biting rust-pitted drums makes him spin round just in time to see what used to be the radiator of a 29 bus baring down on him. He drops to the ground as a hundred plus, sardine-packed, commuters concertina inside and the driver leans hard on his horn. Luckily, God’s blessing – ‘Dios Bendiga Esta Bus’ – plastered in sparkling red, gold and green across the bus’s windscreen, is in full effect. Though it’s a wonder the teenage driver can even see enough through the letterbox of glass that’s free from stickers to spot Pablo at all. But he does and, thankfully, the brakes hold.

Pablo opens his eyes, quickly makes his peace with the two tons of steel bumper hovering inches from his head adn dashes after Marta who he can see disappearing between a taxi and big black four by four.

Pablo catches up with her as she clears the final two lanes of traffic and cuts into Zona Tres heading up undertakers’ alley towards the Basura.

The coffin makers are up early too, stripping down boards of pitch pine. They seem to be the only people in the city – aside from the prostitutes sucking on Coke bottles outside the hole in the wall tiendas – guaranteed work every day.

“Marta.”

Pablo doesn’t want to get to the dump without breaking the silence between them. He doesn’t have the vocabulary to say what he’s feeling, let alone make Marta feel better. But he needs to close the gap.

“I… er…” He’s struggling, but she doesn’t slow down. “The policemen…”

“They’re pigs, Pablo. They’re not men.” Marta’s voice is calm. Scary. Missing the cool assurance Pablo would like to hear. He wishes he had done more to protect her last night.

“I’m sorry,” he says.

“Sorry they didn’t fuck you too?” She spits, swivelling to face him. “Sorry you’re not lying in a mess of blood and bone in that stinking building? There isn’t much more this city can do to me Pablo. I don’t need to watch it eat you too.”

Her outrage frightens him as much as her earlier calm, but it’s also a reassurance of kinds. If Marta’s still concerned about him, maybe things can be okay.

Pablo had feared she would shake him off after the fight with the taxi driver. But she hadn’t. Strictly speaking it hadn’t been Pablo’s fault, but if Marta hadn’t come along when she did, the man would have had Pablo in the back of his car and been off. Even at seven, Pablo knows rides that begin like that are one-way trips.

It was back in the rains. The market traders had been hurriedly packing up and Pablo and Marta and some of the other kids had been trailing through the gutter streams on the look out for runaway tamales or other sea-bound scraps. A taxi driver, out of his car, had caught Pablo’s attention with a click of his tongue and beckoned him over with a ten quetzal note flickered between two fingers. When Pablo had gone over to the man, he had grabbed him by the arm and tried to force him into the car. Marta had seen and she ran over, jumped on the taxista’s back and bit him in the face. Pablo remembers the long line of adults hunched against the rain waiting for their buses. They just stood there, clutching bags of potatoes, doing nothing while a couple of grubby street kids fought a full grown man. It hadn’t even been dark and the marketplace was still busy. The taxi driver had pulled Marta off his back and punched her full in the face. Not with the sort of slap a drunken parent gives an unhappy child, but a full-fist, angry punch that carried the entire weight of his upper body. Marta had flown, like a shot bird, through the air and hit the road lifeless, out cold, blood spread across her face. The driver had dusted himself down like a cowboy – as if he’d been in a real fight with another man – and shot the bus-waiters an exaggerated ‘can-you-believe-these-kids?’ look before getting in his car and driving away.

Marta had been unable to speak, or eat, for days. She’d suck on the soft peaches they’d find when the market closed and spill water down her face from a bottle Pablo would carry for the purpose.

They hadn’t known each other that long before the taxi driver incident, and Pablo had presumed Marta would likely avoid him after the trouble. But she wore the black turning blue then yellow bruises with defiance. She didn’t ask for, or expect, sympathy, but word got round the basura and accorded her some kind of respect. It took weeks for the bruises to creep down her cheeks and finally sneak away beneath her neckline. But, to Pablo, they were a mark of her courage and strength, and a warning to anyone else who may have considered wrangling with her.

Mariano, the old boy with the twisted foot who peddled green oranges outside the covered market, said they were the marks of a street-fighter, and that they didn’t belong on the face of a muchacha. He would cradle Marta’s battered face in his shaking hands and say, “I thought we had seen the last of this,” and other stuff Pablo didn’t get about Marta carrying his “sister’s scars”.

But the old man never chose to flesh out the story, and they took the green oranges he plugged into their hands anyway. Pablo ate the oranges – they burnt Marta’s smashed lips. Sometimes, if he had one, Mariano would give the children an avocado and Marta would suck it until there was nothing left but stone and skin.

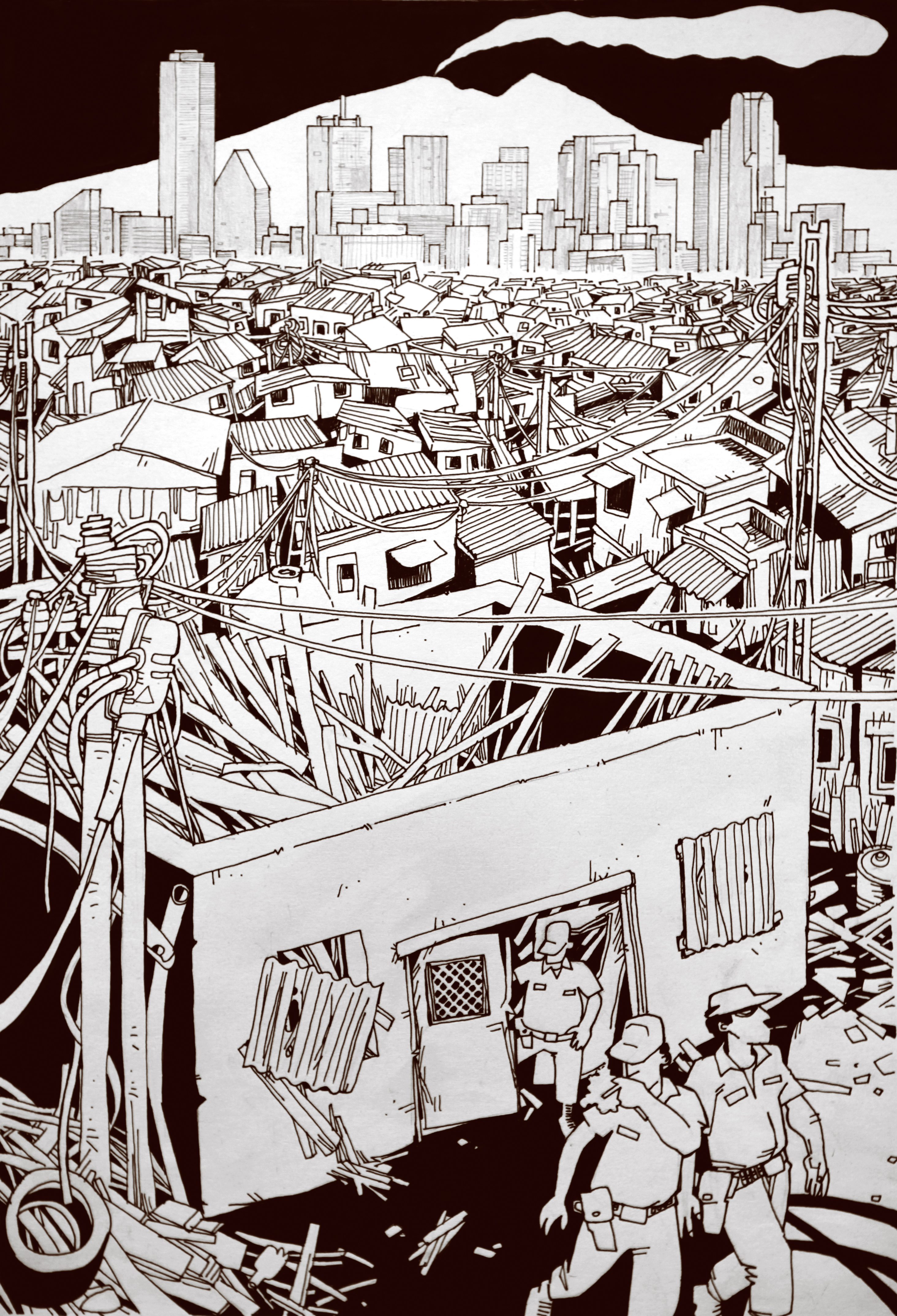

By the wall that runs along the west of the Basura Del Rey, Pablo and Marta come across three uniformed men with shotguns fretfully watching two other men unload cases of Coca Cola and Fresca from a van into the back of a tienda. The fear of robbery is not imagined. The gangs steal anything and shoot anyone who tries to stop them without a first, let alone a second, thought. The guards sneer at the children and play at doing their job.

Diesel oil rainbows leap out of muddy puddles as thunderous buses, that would’ve been broken for scrap in another place, swing out of the zone-three transport yard. Doubtful faces peer from grubby windows. Another day of breakdowns and bullets and they still want to put the fares up.

Next door, the old missionary building, by contrast, is silent. A year of hot beans and bibles had little impact on the Godless-injuns that live off the city’s scraps. Christ, it would appear, has moved on.

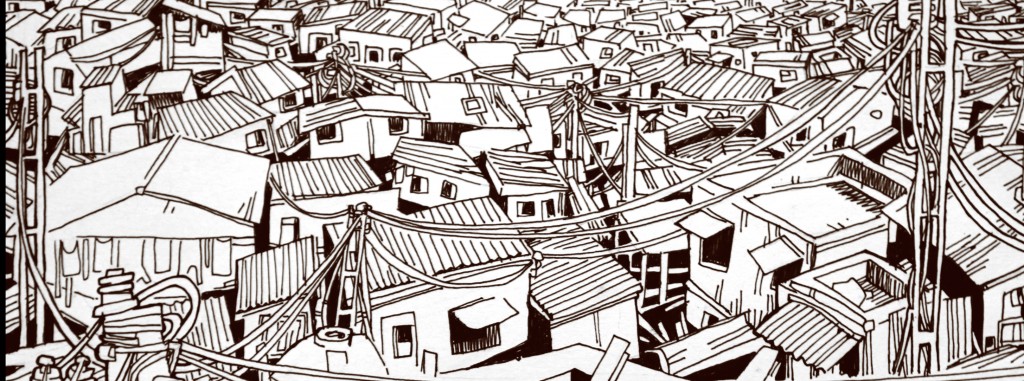

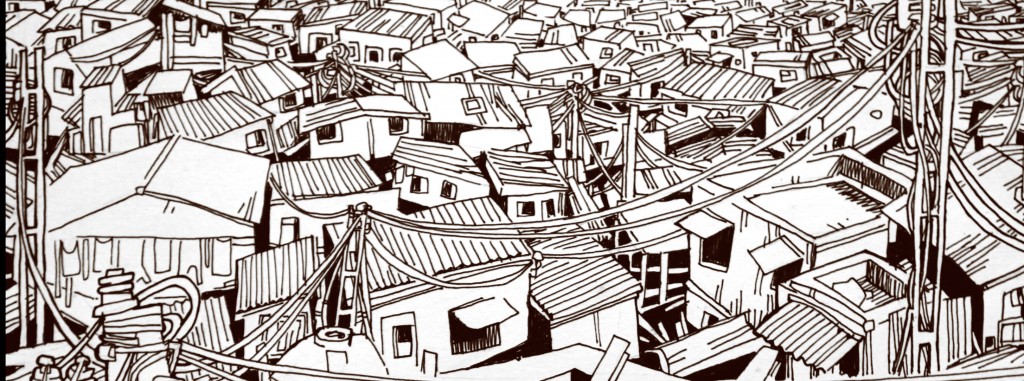

The Reyeno Sanitoria, the Basura Del Rey – The King of the Bins – 150 hectares of rolling, rotting garbage. A mountain of waste the size of a suburb you could see from the moon – if Nasa deemed Guatemala enough of a threat to point a telescope at it.

Marta and Pablo enter through the main gates. The half dozen city guards loafing round the gatehouse, shot-guns shouldered, surgical masks askew, ignore them – four more hands come to scrape a living off what the rest of the city discards.

Pablo coughs as his lungs buckle up for another day sifting air from sludge. The Basura is the home of the Ghost – the clawing, choking cloud of dust that saturates every breath drawn in the barrio. The early morning sunlight, that had been warming Pablo and Marta since they left the rape house, dims from bright white to dull ochre. Above them a thousand turkey vultures circle slowly – a perpetually rotating airborne jail yard, all eyes out for potential loot a hundred feet below. Pablo stops to watch them, his last ritual before it’s heads down at the crap face. As always, he marvels at how they manage to fly wingtip close, eyes fixed on the ground, without knocking each other out of the sky.

“Eagles,” he says.

Normally Marta would contradict him, fulfilling her side of the daily ritual, but today she doesn’t bother. Reality sucks and eagles sounds better than vultures when you’re seven or nine.

An giant rusty bin lorry gives a blast of its horn as the pair dodge in front of it. The lumbering, fume-spewing beast drags itself across the soft surface of the garbage site like a shit-sick dog dragging itself across a shit-stained mattress. The truck looks like it could disappear through the junk crust at any time, but it doesn’t, its half empty tyres appear to help it ride the trash. Behind this one is another and behind that, one more. The slow train of trucks trundles in and out of the dump all day every day, and apart from the odd overzealous guajero disappearing beneath a once knobbly tyre, each drops its twenty ton load and leaves mostly without incident.

The guajeros, as the dump scavengers are known, are waiting. But this is no UN food parcel free for all, there are codes at play here, a system, a hierarchy. The corrugated iron and plastic shacks and sheds that border the south wall of the Reyeno Sanitoria belong to those at the top of the bin-sniffing pyramid. Their tiny yards, are stacked high with cardboard, plastic bottles, glass, metal or paper waiting to be sold on to the recyclers when they come. Commodity collection is strictly demarked – each guajero sticks to collecting his or her own material – some of these businesses were established by families that have been living and working off the dump for generations. The recyclers, in turn, buy their cardboard, plastic or metal from particular scroungers who they know to be good, or at least to have good access – namely first dibs on a freshly emptied truck. Though, it’s true, that the longest established guajeros get the pick of the new lorries, a rotational system of sorts keeps the sunburnt faces in the front line changing.

Many scavengers work in teams, father, mother, son or often just small units of people who have discovered they work well together. Men, with a boy or two in tow, drag snaking mountains of plastic bottles tied with cord across the dumpsite. In other places little caravans of women stagger hunched under stacks of cardboard held by straps to their foreheads. Were Adam Smith’s ghost a dump frequenting kind of spirit, he’d be cackling at the free market micro system being played out daily at the Reyano – all the trappings of capitalism, just without the money trickling down.

A well placed, hard working guajero can earn a lavish fifteen to twenty quetzals a day – about an English pound. Down at the fat end of the food chain, kids and assorted nut jobs contend with the vultures for scraps of food and anything else that’s salvageable and hasn’t been snapped up by the advance guard. This is where Pablo and Marta root, among the orphan loners and crusty ankle biters sent out by their parents or siblings to boost the family pot – an instructive field trip in all but purpose, risk and regularity.

Pablo skips along trying to keep pace with Marta’s fixed stride. Since the older girl took him under her wing, Pablo has got used to letting her make the calls concerning where to eat or sleep or work. He remembers his first days on the dump and how his brother Moses had shown him how to tell a bag of soiled toilet paper from one of kitchen waste without opening it, how they had worked together collecting… was it plastic or cardboard? It seems long ago now and Moses is gone. Pablo is unsure where to, but it doesn’t help to dwell on it. Marta is here now, and Marta is hurting. Even at seven years old Pablo knows everything can change as a result of what happened last night.

“Aqui,” says Marta.

It’s not a particularly good spot. The rubbish appears to be days old if not older. It is damp, but it didn’t rain yesterday. Usually Marta’s pretty sharp about picking bountiful places to dig. Today she doesn’t seem to care. The normal opener would be Marta whipping a full tin of meat, or some wire, or a recyclable bottle out of the mess with an i-told-you-so-ish grin. But this morning, the cue seems to be Pablo’s. He scours the ground. He desperately wants to find something, anything, to please Marta, to show her he is useful and is worth keeping close. He roots around, the panic rising inside him. Come on Pablo. He sees a large blue sack only partially torn, like one from the dustbins of a restaurant or café. He pulls it towards himself and drags out some yellowing vegetable tops and buried inside a shard of broken glass.

He stares at the blood as it runs across his hand and down his wrist. He looks at Marta. She doesn’t move. He has no idea what to do.

“Well done Pablo,” she says without any trace of emotion. Pablo is convinced he’s stacked it and begins to shake. He knows tears aren’t far behind. She takes his wrist, inspecting the cut, but there is none of the cradling or the purring or the ‘mi pobre Pablitos’ he has become used to from Marta when he hurts himself. She’s stone cold.

“It hurts.”

“Everything hurts, Pablo,” she says. The promised tears start to run down Pablo’s face. He tries to ignore them. “If you keep acting like a weakling, you’re screwed. The city will eat you up. It’s blood Pablo, you cut your skin, you bleed. You drop your guard they will pick your bones.”

“The eagles?”

“Vultures Pablo, they’re fucking vultures. But they’re the least of your worries. I’m not helping you Pablo by mothering you like some stupid toddler. ‘Where will we work Marta, where will we sleep Marta, what will we eat Marta? Marta, Marta, Marta!’ You need to buckle up Pablo, stand on your own two feet. Look at you, crying like a baby. You need to snap out of it! And so do I.”

As she talks Marta wipes the blood roughly from Pablo’s cut and tears a strip from the bottom of his t-shirt and binds the wound. Tears roll unchecked down her own face, but she looks annoyed that she’s allowed them to come.

“Look I can’t look after us both,” she says. “I can’t even look after myself. Just go. Go on. Piss off!” She turns away walks a few yards, then bends to the tip tearing at bags and bits of metal. Pablo is frozen. His fear is so acute his tears have stopped, along with his breath. He turns, stumbles a few paces, then runs, falls, gets up and keeps running. When he is thirty feet away he manages to gag down a lungful of air, which is closely followed by a torrent of retching sobs and a damn break of tears.

The cameras weren’t rolling when the bullets started flying, so the world failed to notice a nation having its soul ripped out. By the time Central American genocide hit the headlines, Uncle Sam’s firestorm was already in El Salvador and spreading.

Like all rapes, the violation of Guatemala left its legacy. Communities rent, families torn, people broken. The temples are maintained for the tourists, but the Mam, the Tzutuhil, the Quiche, the Ixil, Kekchi and Cakchiquel or any one of the 28 indigenous Mayan groups whose ancestral lands fall within Guatemala’s borders were left fragmented and fearful. Those strong enough to entertain, let alone voice, a social conscience were slaughtered. Those that are left, look obediently to their bibles and cower at the coat tails of what must surely be a vengeful God – Himself a legacy of the Spaniards who, themselves, raped and slaughtered their way through the country 400 years before.

Bent politicians and Pennsylvania Avenue puppets have remained in power. There was no glorious revolution here. White faced men in western suits have continued to steal and to cheat the brown skin Mayan and mestizo people who populate every acre of the country that isn’t ensconced in razor wire. In the countryside you keep your head down and your hoe scratching, hoping that this year’s maize and beans will be enough to feed the family. But here, in the eye of the storm, in the sprawl and the filth and the fumes of the city, the fear comes to life: in the trembling claw of a grandmother as she stoops to lift a chicken bone from a sea of garbage; in the sweat polished brow of a young security guard given a shotgun and told to scan the faces of those who have come to buy bread; it is in the wild eye of a teenage thief and the gaping mouth of the man who’s head he opens with a pistol he can barely lift; it is in the roar of the traffic and the kerosene stench of the cooking fires; it is in every creeping shadow and every distant bark; it is branded on the soul of the young girl of ten raped in a derelict yard in the heart of Zona Sete. It is in the fetid laughs of the cops who held her and watched and waited as their buddies took turns. It is in the pit of Pablo’s stomach as he cries without comfort. It is all that’s left now the love and the trust they shared has gone.

Pablo climbs up the dump side, away from the swarm of activity below. The trash up here is ancient, long sifted and resifted, anything recyclable long ago extracted, anything edible long ago eaten. It’s just waiting for the trucks to return to this side to be buried beneath the next strata of landfill. Ten thousand years from now this place will make archaeologists pee.

Pablo climbs until the noise of the lorries is little more than a buzz and Marta is just one more louse scouring the smoking, seething host below. Pablo sits and sobs under his own personal doom-cloud. But the adrenalin soon subsides and the tears ebb away and before long his mind is wandering, unable to stay locked onto this latest desperate turn of events for long. He is, after all, still a little boy.

The guajeros bent to their task below remind Pablo of his father, turning the soil to plant marrows beneath his coffee plants on their small patch of land on the banks of the Rio Santa Isabel in the Alta Verapaz. As the insects buzzed and the hoe tore at the ground, Pablo would follow his father’s hands picking out the weeds, flicking the stones aside. When the coffee was ripe he would follow his mother’s lead as she scooped the reddening fruit from the bushes into her gathered apron. She is young and very, very beautiful, but Pablo shies away from conjuring up an exact rendering of her face. He can’t quite make out the details, the curve of her nose, the colour of her skin. He remembers her long black hair, tied in a pony tail, like Marta’s, or is it a plait? He remembers himself standing on a wooden box in order to reach the turning handle of the shelling machine. His mother would pour the red beans in the top as his father held the sack to catch the shelled white beans below, encouraging his only child to put his back into turning the handle. ‘Mas fuerte tigre,’ with a flash of gold in a weathered smile. For the first time that day Pablo also smiles as his mind paints pictures of coffee beans tumbling into the midst of a loving family. His eyes roam the dump crust turning the shadows and shapes to fit the scenes in his head: a veg crate palm tree, a carrier bag bush, distant scavengers become close up chickens, a passing breeze sweeps a paper-chase river meandering through the mess, a nest cradling a fresh laid egg. Pablo’s wandering mind snaps suddenly back to the present. Fifteen feet from where he is perched, Pablo’s eyes have fallen on what appears to be a deliberately constructed circle of plastic and paper and splinters of wood. A nest. And in the centre, shiny and dark – is an egg.

Pablo looks up at the trawling swirl of vultures. Then back at the nest. Stooped, as if less conspicuous from above with a hunched back, he scrambles over to the edge of the nest. The circle is large, even if he stretched out Pablo could still lie inside it, but then the eagles are not small. Neither is the egg. The egg, sits in the middle of the construction, its dark shell glinting in the few rays of sunlight penetrating the dump’s curdled brown air. It is much larger than the hens’ eggs in the market and not white or beige but dark – black with a mottled patterning of gold or green or blue depending on how the light hits it. It is the most beautiful thing Pablo has ever seen in this dump and he is fixated by it.

He watches it for a while perched at the edge of the nest. But he does not go in. He does not touch it. Instead he retreats to his vantage point and waits for the mother bird to return. He has a long wait.

Marta lets the cockroach scurry across her hand. She does not play with it, but she does not shake it off, as she would have yesterday. She thought she was immune to the city’s poison, she has after all witnessed plenty of pain in the few years she has been here, felt plenty too. She had felt plenty before she left home. She thinks of other insects – the butterflies busy going nowhere in and out of the lemon trees that grew on the slopes behind her grandmother’s house. Petalos perditos, lost petals, the old woman had called them – while she still had eyes to see and a mind to register simple thoughts. It was one of the few things that made the old bird smile, flickering shocks of blue iridescence snaking about the yellowing leaves and deep green fruit.

Boys from the village would goad the pack dogs that skulked at the edge of the pueblo to leap up and snatch the butterflies out of the air, then fall about laughing as the moronic animals would twist and spit and retch, unable to shake off the papery wings that stuck to their tongues. The boys never tired of the trick and the dogs seemed too stupid to remember how little they liked the taste of butterflies the last time it was played on them. Beautiful to look at, but not much use in a fight. The butterflies were doomed from the start. There’s no place for such things in this world thinks Marta. They died, confused and broken and bleeding. Just like her grandmother. Just like her mother.

Marta had cried for a while after sending Pablo scurrying off across the tip. But the dry sobs had sounded too much like self pity, so she had stopped. She knew she was bleeding, she could feel the blood on her legs, she could feel the searing pain between them. As she bent to sift the rubbish, knives twisted inside her belly and a hammer pounded inside her head. She was struggling to stand, she was struggling to stand it. She hoped she was dying. She was tired of waking up and wading through the detritus of other people’s lives. Tired of being a punch bag for men too scared to hit their own wives, or too proud to jerk off, or too selfish to stay home, or too weak to stand up to their buddies or too stupid to kill themselves.

Marta sits down on a shredded lorry tire, ignoring its spindly wire fingers as they claw at her thighs. She can see Pablo high on the western bank of the basura, his head now out of his hands, something else has caught his attention. She is relieved he’s no longer upset, but checks herself. It is not her place to care. She can’t support him any longer. She had fabricated some sort of bubble around them both, or thought she had at least – but it was just imagined. She was a fool to think that she could protect him, or her, with a few tortillas and a blanket and a salvaged pair of oil-stained sandals. They were kids playing a game in a place where no one else is playing. Where no one else stays kids for long. Sheltering Pablo from the fury of the city was making him weak, making him think things will get better, making him believe things could be okay. Things were not going to get better, and were not going to be okay. Pablo had to wise up to that and so did she.

Marta looks at the loot at her feet – three plastic bottles and something that might be a kettle. The first food usually went straight into Pablo’s ever-open beak. She feels sick. Blood runs down her ankle and onto the heel of her flip flop. She needs to wash. She needs to be somewhere else.

Chapter 3.

Pablo hadn’t seen Marta sit and watch him, and he hadn’t seen her collapse slumped on an old tyre way below. He hadn’t seen the two women who came and led her out of the Sanitoria and into the web of narrow paths that separate the tin and cardboard shacks of La Libertad – the flimsy shanty thrown together on last year’s landfill. He had been watching the birds. He watches them all day.

He studies the crazy jubilee above him, and tries to locate the one bobbing head, the one black shadow that must be the wary parent of the lonely egg in the giant nest. At one point he thinks he’s found them when a pair of the vultures dive out of the turning circle. But they clatter down far from the nest and instead squabble drunkenly over the garbage from the hospital truck, wings flapping like toddlers’ arms in a guardia fight.

Pablo is hungry, he has not eaten and has nothing of value to trade for money or food. He hasn’t even looked. How late is it? It has already begun to cool, the sun is a little dimmer, on the way down – the city switches fast from furnace to freeze up now winter is here. Marta can sort him out.

He scans the creepy crawlies below. He can’t see her. He feels his skin chill and waves of goosebumps form and ride up his arms and back. He tries to consider his options before they break on his shoulders and drag what little power of evaluation he has left into the rip. A final shot look into the madness of the bird cloud convinces him he must save the egg. The mother has gone, dead, deserted, with a new egg in a new nest? The tiny life inside this one is in Pablo’s hands now. Four leaps and he’s at the nest edge. One more and he’s inside. He picks up the egg. It is warm, from its day in the sun, and much heavier than he expected, it’s shell rougher than it appeared from a distance. Pablo rolls the tiny life into his grimey t-shirt until only the mouse’s faded round ears are visible above his, now exposed, skinny brown belly. Then he changes his mind. He has a deep pocket inside his shorts that Marta stitched one night about a month ago so he could hide any money he made, or anything else that needed hiding. He takes the egg out of his shirt, unbuttons his shorts and puts it into the pouch. Pablo remembers he is still in the nest and glances upwards expecting to see a pair of talons cming in for the kill, but the eagle wheel is in place, unbroken fifty meters above. He buttons up, hops out of the nest and heads down the bank towards the exit. The egg clumps reassuringly against his thigh, the fear wave subsides, and Pablo’s skin goes back to keeping his blood and bones in place.

Marta had made no attempt to explain why she had collapsed to the two guajeras who brought her out of the dump. But all three women know well enough what has gone down. Does being raped make Marta a woman? Does any man have the power to make a girl a woman? Marta hopes not. But there is no currency in clinging to childhood in this town. If she didn’t know that before, she is sure of it now. She sips the hot sweet coffee and studies the lettering on the cardboard boxes that constitute the dividing wall between this shack and its neighbour. She cannot read as such, but she recognises some of the logos – Johnson and Johnson, Nestle, General Motors. A half dozen or so boxes declare themselves the ‘Product of the Coca Cola Company’. She knows that one – the red and white swirl has replaced the blue and white flag as the national emblem. Guatemala – a product of the Coca Cola Company. Black toothed smiles – better than no smiles – and the sugar hit could usually turn up the corners on even the sourest of mouths.

The names remind Marta of the factories that line the Pan American highway as it dives towards the city. She had taken a bus along that road with a woman called Doralisia. They had travelled together from Concepcion, the village in the Cordillera de Cuchuman where Marta had been born and raised until her mother died and her father split and before that bastard uncle of her’s had…

Half the people on that bus were escaping their own private hell. Doralisia was no exception. She had pointed out the factories that lined the roadside where she hoped to find work. The pay was not good, she had said, but it was money and it was somewhere else. They had stayed together for a few days, but both girl and woman had felt they were carrying the other so had agreed to part company. Marta had seen Doralisia some months later. She was pregnant and had been sacked from her job driving a sowing machine for Wal Mart. Marta thinks she may have gone back to Concepcion, though someone had told her she had seen Doralisia turning tricks on the Diagonal. Marta likes to think she went back, but knows deep down she didn’t.

“Heh Pablo! Que haces chingon?” It’s Moreno, a likeable halfwit from the dump. Moreno is a cardboard scrounger, or at least he works with his uncle who is a cardboard scrounger. Cardboard is the most sought after recyclable in the Sanitoria. Glass, metal, plastic bottles, all good, but the cardboard boys are at the top of the tree. Moreno’s uncle works with three other guajeros, they build bales of old boxes and tie them with string and sell them to one of the recyclers that cluster near the dump gates. It is a locked shop and the cardboard collectors protect their positions jealously.

Moreno is lucky to be on board, or so they constantly remind him. Truth is he doesn’t really care. His mother scolds him, tells him he doesn’t have enough foresight to secure his place in the cardboard hierarchy. Pablo thinks maybe he has too much. Either way Moreno has no ambitions for work either in or out of the dump. Moreno’s sole concern is where the next bag of pagamente is coming from. Awkward and confused in the real world, Moreno is only at home with a head full of shoe glue. And he’s not alone. Half the kids in this neighbourhood are sniffing it.

“Come on,” he says to Pablo. “Let’s go to my place.” The two lads cut back past the Sanitoria, weaving their way through a squawking group of plastic-collectors dragging a snaking mass of string tied bottles back to La Libertad.

Moreno, followed closely by Pablo, dodges through a gap in the shacks no wider than a man’s shoulders and along an alley. Kids and dogs litter the tiny street. The boys cut left then right into a slightly wider alley, a main thoroughfare. A 1000 volt low-tension electricity cable has fallen from its posts, weighed down by the web of home-clamped wires bleeding power into the shacks below. If Marta was here she would tell them not to touch the cable, she would tell the small boy using the wire as a road for his plastic car to go and play somewhere else. She would repeat the story of the man she saw electrocuted cutting into the power supply and how his body had jerked and twisted like a puppet tugged by strings, and how it had fallen through the roof of his home to the ground where it had smoked like charred meat. Moreno steps along the cable arms outstretched like a tightrope walker, Pablo follows him along the ‘highwire’. The small boy drives his car along his makeshift road.

Rosa is cooking beans in a pot over a can of kerosene when Moreno bundles into the tiny shack. She greets her son in the global manner adopted by mums zoo-keeping unco-operative children – with a loaded question she already knows the answer to.

“How did it go today with your uncle?” Moreno has two ways to answer. He can accept the collar and plead some kind of mitigation or he can go the road favoured by the majority of his cross-continental counterparts.

“Okay,” he lies. Even Pablo with his limited experience of family interaction knows he’s a dead man, and he’s witnessed this same gunfight in this same corral several times before. Despite the red of her shawl, Rosa is always the man in black. She swivels slowly from her bean pot. The other children, who had been playing on the small section of threadbare, salvaged carpet that covers a corner of the dump dusty floor, stop their game. All eyes are on Rosa as she crosses the few feet to where Moreno has sat down on a crate. He knows if he stands he would be just that little bit taller than his mother, but now is not the time to be tall. She glares, he shrinks. Rosa has sureshot timing.

“I tell you what Martin,” her voice is calm and slow and scarily quiet. She is the only person, in or out of the family, who ever uses his given name. “We’ll just eat your shoes today will we? Tomorrow we could maybe eat, hmmm… the radio, perhaps one of the ninas t-shirts or a blanket from the bed. We could keep going till we are all naked and have no home left.”

“We could eat the chicken,” he says. All eyes pan round to the chicken that has chosen that moment to march robotically out from its place under the bed. Though chickens are a regular sight in the barrio, this bird looks strangely magnificent high stepping like a Spanish stallion, the deep reds and golds of its plummage shimmering in the lamplight. Moreno’s three year old brother Raul, grubby and naked apart from a ragged pair of shorts, peers over the edge of the bed just above the bird. The urchin and the feathered idol make for quite a sight.

“Let’s eat the chicken!” bellows Rosa. Calm over, storm kicks in. “Yes that’s right! You dick around all the day sniffing glue with your dim-witted chums and we’ll eat our only source of regular food, and then we’ll starve! Que bonita idée!” The speech comes more from a sense of her parental duty to reprimand her offspring – she doesn’t genuinely expect to change Moreno’s outlook or his indolence. That said, despite her brother’s generosity in employing an airhead like Moreno, if the boy doesn’t work, no money comes in. She clouts him round the head, though not hard enough to really hurt. Moreno knows this is her final gesture and relaxes and slides off his crate stool.

Rosa turns to Pablo still standing in the doorway. “Pablo… Pablito… Vengas. Come in. Come into our home.” Despite the shadows beneath her eyes and the lines that fracture her face like muddy rings in a bus-bounced puddle, Rosa is only 28. She has five children and is considered an old hand by her neighbours, but would be considered a young mum 2000 miles to the north.

She takes a small clay figure from the cramped shrine that sits on the shelf between the smoky yellow glow of the stove and the silently pulsating blue lights of the family’s oversized plastic stereo. The figurine depicts a small man sitting, his head is disproportionately big and on it he wears a huge headdress shaped like an ear of maize.

“Like Yumil Kaxob, the corn god,” she says bending to Pablo and running her finger along a scar cut into the figure’s tiny face. “We are at the mercy of more powerful elements.” She casts a last evil-looking eye Moreno’s way before replacing Yumil Kaxob among his companions. Pablo smiles. It is only a little thing, but it is between Rosa and him.

He likes Rosa’s shrine, though he is not allowed to touch the figures. No one is, not the children of the family or even Moreno’s uncle. But he knows them all. Behind Yumil Kaxob stands Gukumatz, the quetzal feathered serpent and bringer of peace, to his right, Ah Kinchil, the kneeling sun god, and to his left Ix Chel, the ancient moon goddess in her skirt of many crossed bones. His eyes flick from one clay figurine to the next, resting a second or two for recognition, a tiny greeting, then moving on. It is a reassuring memory game, something samey in a life with too many recent changes. There is the skeletal Ah Puch, the deathly god of the underworld, feathered Kukulcan the god of the wind, Chac the rain god snake, Ixtab the suicide goddess with a rope around her neck.

Rosa watches the small boy’s eyes as they shift between the tiny icons, she waits until he completes the exercise and for him to break his own concentration, then she leads him to the table in the corner of the shack where food is prepared. She buries her hand into a folded bundle of faded pink paper and pulls out a single tortilla. She thrusts it into his hand. “You are like Ah Puch, a bag of bones. You will eat with us tonight Pablo.”

Moreno climbs onto the bed and begins winding up little Raul who’s easily excitable after a day under Rosa’s heels. The commotion triggers a snarl from Rosa, and Moreno, remembering Rosa’s ice is still fairly thin, reins the toddler in with some less manic toe counting.

Pablo drops down to where the two girls are playing on the rug. Olga Isabel, known to everyone as Chiqui is three or maybe four years old and is listening intently to her older sister Marisol. Marisol is trying to teach her younger sibling a song she learnt in school that day. Marisol pretends not to notice the arrival of the extra pupil, but Chiqui appreciates the increased effort of her teacher.

Marisol sings, Chiqui imitates and Pablo laughs. It isn’t long before the girls have him performing too. The day’s events seem far away. Pablo thinks he will show them the egg after they have eaten. He feels right at home. The arrival of Moreno’s uncle Luis quickly snuffs out that particular candle.

Luis, six foot of dump-hardened bitterness with less teeth than remaining fingers stands in the doorway and waits until everyone knows he is there before pushing the plastic sheeting back into place behind him. The stench of garbage and smoke follows him in.

“Very cozy.” His words are aimed at Moreno, who instinctively drops Raul’s foot back onto the bed. The two boys retreat to one end of it. Luis sits himself at the other. Rosa hands him a beaker of hot sugary coffee.

“He will be at work tomorrow,” it is not a suggestion. “Or swimming in the gutter with the rest of the trash.” Pablo can feel Luis’s eyes on him, but does not look up. Even at the frayed end of society’s rope, he is aware that people find comfort by sneering at those who don’t have quite as tight a grip as they do. Rosa says nothing. In the past she has defended Pablo in front of Luis, but Luis doesn’t like it, and she is reluctant to rile him any more today. They need his input, especially with another baby on the way.

Rosa dishes each of them out a small bowl of rice and beans and a tortilla to eat them with. Pablo wolfs his food down. Luis takes his time.

“Two more boys from the zone have disappeared from the dump,” he tells Rosa, who does not eat herself, but sits watching the rest of them.

“It’s the Man with the Golden Boots,” offers Moreno through a mouthful of beans. “Vicente’s brother said he saw him last week at nightfall. He said he is as tall as a horse.”

Luis brushes the comment aside. “And has Vicente ever seen a horse? Fairy tales don’t take children you idiot. You keep wandering around with your head in a bag, some bastard will get you too.”

“Luis is right you should be careful,” adds Rosa, her eyes drawn to where Pablo and the girls are sat. “All of you.”

“I’m not scared of anything,” says Moreno, standing.

“Not aware of anything more like,” says Luis.

“Come on Pablo. Let’s go.”

Pablo runs a mucky finger around his bowl and sucks the last of the frijoles and a weeks worth of grime off it. He hands it to Rosa. She secretes another tortilla into his hand and ruffles his hair. Pablo wants to tell her about the egg, the weight of it against his thigh is begging for attention. He wants to tell them all that he has found something that can keep him safe, keep them all safe, from Golden Boots, from the gangs, from being hungry, from being scared. But Luis’s stony look is all the reminding he needs that he doesn’t really belong here. He allows himself a quick goodbye glance and a mumbled farewell to Chiqui and Marisol.

“Cuidate champin,” Marisol calls out. Pablo blushes, embarrassed by the familiarity, and scampers after Moreno into the fading light. Champin? Not really suitable for a boy from the southern lowlands.

He would like Rosa for a mother he thinks, but she is very different to his own. His mother was… younger, prettier, funnier, less harassed. She would sing to him, just like Marisol sings, as she would rock him to sleep on her lap. She smelt like the flowermarket in the morning – he can remember that clearly – if you took all the people and the garbage away. And she had a husband. Rosa had a husband too, but it turned out he had another wife somewhere else and when Rosa became pregnant again he went to live with her.

Pablo follows the older boy through the darkening alleys of La Libertad, their way lit by the occasional escaped light shard sneaking through a crack in a wall or a badly fitting tin door. The shacks are fashioned from all sorts – salvaged wood, ply, corrugated iron, cardboard. Some have block walls and a few a second storey. A group of children wait to fill plastic jugs and buckets at a standpipe – there’s none of your bug-free bottled water here – the spilt water runs beneath their feet and under the wall of an old woman’s home. Kerosene and wood smoke seep from the eves of the shacks as if the shantytown is exhaling, glad to have survived another day. Somewhere, someone is cooking something that smells like chicken and there is another smell, a sweet smell, that always plays favourably across Pablo’s nostrils for the few moments it takes him to place it. It’s the sewage that seeps from the ground at the bottom of the slope. In this neck of La Libertad fifty families, with six or seven members in each, share three toilets between them.

Moreno weaves through the lanes, cutting right, left, right – his characteristic dimness forgotten in his hurry to get where he’s going. They emerge from the mess of shacks and cross the campo, deserted save for a group of hooded youths smoking under the farthest goalposts. The lads keep their distance circling the pitch and hopping a low wall on the far side.

“Diez y ocho,” whispers Moreno. Gang kids, they had to belong to either the Eighteen or the M.S.

“Si.” Even in the half dark and at a distance, Pablo is reluctant to look at the gang members. But he does recognise the hunched boxcar outline of a big youth they call Yomango.

The lads follow the perimeter of the dusty football pitch to the far end, then cut through some scrub bushes and drop down into a hole. The space is rectangular and similar in size to Rosa’s place. It looks like a house had tried to grow here once but had given up after poking a dozen rusty fingers up through the concrete floor. Pablo reckons the smell probably made it go and look for another spot. Now the fingers are bent and rusted and buried in litter, leaves and undergrowth.

Moreno is in a corner fishing beneath some stones. He finds the pagamente he bought earlier from one of the shoeshine boys that live in the barrio.

“Get some bags,” he tells Pablo who doesn’t need to look far to find a couple of small clear carrier bags with straws poking out. Guatemalan snowflakes – little clear sacks that once held colas – the only things in these streets that outnumber the rats.

Moreno pours a dollop of the caramel-like glue into each bag. The odour of industrial shoemaking sends waves of both dread and expectancy through Pablo. He doesn’t really know why he’s here again, but he has nowhere else to go and no one else to be with. He takes his time finding a place to sit, getting comfortable, wondering aloud if the gang from the park may follow them to this place. But Moreno is not stalling. He has his mouth and nose in his bag and is breathing steadily. The bag expands and contracts like a ventilator at the bedside of a dying child. He slides his back down the wall, not bothered where he sits. He is not listening to Pablo. So Pablo shuts up.

Out of diversions, Pablo puts the bag to his lips. The harsh chemical vapour barges the dump dust in his throat aside. Clenching the neck of the bag over his mouth and nose Pablo cradles the body of it in his hand and begins to breathe. In… out… in… out… Panic subsides as the toluene makes a cushion out of the concrete floor and pulls a fat furry blanket up tight around his neck and face.

Pablo tumbles with the glue down the familiar, buzzing vortex. Cycles of sound begin a regular, roughly-identifiable, rhythm – a tidal suck and blow. In again, out again, on again, off again. Round and around. Rosa’s voice scolds and Marisol’s laughs, then tuts at Pablo’s increasingly blasted state. Marta, still angry, walks away. And something else. Something else is in there. Something different. Something new. Something growing and glowing. The shock of seeing the egg is enough to earth Pablo momentarily, to bring him back to the campo house, to catch a glimpse of Moreno neck deep in his own stuttering, lunatic meanderings.

But reality can’t hold him long and the egg in Pablo’s head is getting bigger and more and more amazing, and though still dark, wherever Pablo focuses on the shell myriad colours seem to chase each other in and out of the black, mixing and twisting as if drawn with a stick in oil on water. Despite its blackness, the egg glows like a hot coal in the fire. Bright, burning, red geometric lines, map across the now house-sized, now city-sized egg, dividing then reuniting patches of swirling darkness. Pablo knows the heat and the light inside comes from a new life, a growing, strengthening hope. A flaming golden eagle that can take Pablo in its talons, place him on its back, and away. Away from the dump and the dust and the fear and loneliness. Marta too. Pablo and Marta together, safe. He never had anything to offer her before, she had always been the one with the ins and the outs. But now he, Pablo, has the answer. He can make it better. Whatever has happened, the egg can make it good. The eagle will take them back to the hills, or is it the coast, to his father’s farm, to his mother’s warm embrace. And there she is. Beside the egg. She is old, grey hair tied up on top of her head. In her hands is an enormous basket of mandarins, she puts it down at her feet, crouches and takes one out and begins to peel it for him. She looks a lot like Rosa, but with Marta’s smile. She hands him the mandarin. It is an egg, the egg. And it is hatching, and a tiny perfect eagle stands in his hand. It spreads its wings and launches itself into the air growing bigger and stronger and golder with each wing beat. It wheels around, revelling in its discovered freedom with an drum busting shriek. It swoops down and scoops them up with its wings. His mother smiles, she is happy her son is coming home. And Pablo is happy to have finally found the way.

Chapter 4.

It is several hours later when a sadistic consciousness drags Pablo out of his spanner-brained dreamstate and back to the half house. Moreno has gone, but the fear is back. The toluene is all funned out but has stuck around for payment. Pagamente. Tiempo pagar. The glue has left a scabby halo around Pablo’s mouth, the inside of which tastes, literally, like an old man’s shoe. His head hurts. It’s dark, it is cold and he is shaking. As is the way with all drug use, the come down doesn’t feature in the prelude or the execution. But once those dogs have eaten and split, it’s the whole of the show.

Pablo stays in his spot in the old foundation trying to rationalise each sound and keep his panic on a leash. He is just another rock, an unfinished plinth, a random pile of concrete or a misshapen shrub. Nothing to take a second look at. Nothing to interest man or animal. The flow of traffic a half mile away on the EJE1 provides some comfort – the sound of the city’s disinterest in this one small boy. The unexplainable snaps, cracks, barks and occasional gunshots are much closer and much less easy to shelve. Pablo sits in the darkness clutching the egg. He’s on his own little ghost train. Every couple of minutes a howling fear bursts through the glue fug brandishing an imagined hatchet, or a pistol, or a pair of golden boots. Despite their repetition and regularity, Pablo is unable to brace for their impact or predict their passing. He is seven years old. He is alone. He wishes more than anything that Marta was here.

Despite the cold and the numbness in his legs and his bottom Pablo stays in his spot motionless aside from his ragged adhesive breathing. An hour without incident ratchets the gaps between his panic attacks wide enough to allow for some other brain activity.

The egg, in its pouch against his thigh feels warm. He unbuttons his shorts and takes it out but, despite the darkness, he is uncomfortable with having it exposed, so he puts it away again. He thinks about the mother eagle, and whether it returned to the nest disoriented by the loss of its unborn offspring. Does his own mother wake at this hour and wonder where her son is? He thinks of how the egg bird will lead him back to her. For a moment the complete irrationality of this thought flashes before him, but Pablo’s self protective override is quick to nip such thoughts in the bud. Harsh realities, after all, have no useful purpose in this place.

Several times he is snapped back to the house hole, back to the moment, by a sound or a change in the breeze or a fear or a tiny movement from inside the egg. The eagle is growing, getting stronger. It too knows about the job at hand.

Pablo risks a shift to allow some fresh blood into his cold, numb legs. Another hour unmolested, a result – of sorts. Fanciful meanderings give way to tangible confusion and hunger and what an older, more world weary, man would call self-loathing. Pablo just feels lonely and lost.

A wash of light from the east of the city rumbles the shrubs and rock piles that spent the last hours masquerading as wolves and pistol whipping gang boys. Pablo gets up. The growing light convinces him it’s finally safe enough to pee – the last of his body warmth splashing into the undergrowth making him shudder like a wet dog. It feels like weeks ago that he was in Rosa’s shack eating tortillas and beans. A month since he last saw Marta. A year since she hugged him.

The prospect of leaving the comparative safety of the anti-house zaps Pablo with a fear-fuelled reminder he’s still just a little boy spinning out of a glue trip. On the spur of the moment he decides to hide the egg.

Around the edge of the concrete base are columns of steel, erratic-lengthed clusters of rusty metal rods tied into box sections with thinner, equally rusty, wire. Pablo is used to seeing these brown clumps jutting out the top of small buildings whose owners are still saving to build a second storey. Some of the columns have been encased in concrete, some rise out of the concrete at ground level, and one or two – at the more overgrown end of the house-base never got their concrete jackets at all. Here the rods have been driven into the ground, the wooden boards that had shuttered them in ready for the mix that never came have long since rotted away. Pablo bends to one of these square holes and puts his hand down inside, it is soft, full of several autumns’ fallen leaves. He gathers some more leaves and attempts to uncrush a small discarded cardboard box that once contained formula milk and bares the unlikely, faded picture of a pink grinning baby on it. He puts some of the leaves into the box, then carefully takes the egg from his pouch. He turns it over in his hands, half surprised that the shell isn’t dancing with the rainbow patterns he had pictured last night. But he is still awed by its beauty, its solidness, its precision. It looks unbreakable but he places it in the box of leaves with the utmost of care all the same.

A shiver blows like a warning through Pablo’s body. He spins round surprised by the absence of a lurking thief. He quickly covers the egg with more leaves, then slots the box into the steel rod column and down into the hole. He piles more leaves on top, stands back, takes some out again, stands back again, puts two back in, and is finally happy.

He scans the last of the shadows, turning half circles over his left, then his right shoulder – like a cartoon pirate with a sandy shovel. Satisfied, to an extent, that no one has seen him and that the egg is as safe as anything, or anyone, can be in this part of town. He hops out of the house hole, through the scrub and onto the campo. Once on the football pitch he begins to run. By the time daylight breaks for real on La Libertad, he is on the other side of the zone.

“Gramajo, didn’t that bastard end up in some fancy beachfront house in Florida with the rest of the torturistas.”

Marta is in the house of Esperanza, a small concrete building with bars on the windows. This is where the two guajeras brought her yesterday and cleaned her up. Present are Esperanza and her friend Lilian. On one wall is a hand-painted banner that reads ‘Mujeres Contra Violencia Guatemalteco’, Guatemalan Women Against Violence. Inside the two women and the girl sit at a table. A small television set in the corner of the room shows pictures of the new Minister for Internal Affairs. Manuel Sanidro Gramajo.

“Who is Gramajo?” asks Marta.

“Don’t ask,” replies Lilian.

“He was a General in charge of the some of the worst killing,” says Esperanza. “Him and his friends from el Norte taught his men to break women.”

Marta’s look betrays her puzzlement.

“Beat, burn, rape, murder them. And their children in front of them,” Esperanza makes no attempt to hide her contempt. “Put cigarettes out on their faces, in their ears, on their breasts.”

“Esperanza,” chides Lilian standing and going to the stove.

“Gramajo’s mark was to go to a village he suspected of helping the resistance and slit every throat, big or small,” says Esperanza. “They would fill a pit with corpses then throw young girls in on top. They would take a machete put it in a woman’s hand and force her hand to bury it in her daughter’s belly.”

“Enough,” says Lilian. “The girl does not need to hear this now.”

Esperanza makes a huffing sound. “Anyway, that’s Gramajo. The Yanquis rewarded him with a house in the bay and a fancy education at a marble university.”

Esperanza’s home is sparse but clean. Aside from the table and the sideboard, the room contains three straw mattress beds, one on a bench and two on the floor for, Marta was told last night, ‘women who need them’. She had slept in one of these. Esperanza had slept in the other room. Where did Pablo sleep?

“And now he’s in the government,” says Lilian scraping scrambled eggs from a pan onto a plate with rice and beans and putting it down in front of Marta. “It’s the same old story.” She goes to a shelf and brings a plate, and a small paper bag and puts them on the table. She takes a handful of tortillas out of a paper bag and puts them on the plate.

“Comete nina,” she says. Marta wonders when Pablo last ate.

“Thank you,” says Marta. “Did a lot of people die?”

“Many.”

“And?”

“And the killers are still out there. In the army, the police. On the streets.”

The residue of the pagamente is like a second skin inside Pablo’s mouth. It feels like something similar is going on inside his head.

He thinks of Marta, angry, sending him away the day before. But he finds if he takes the image, shrinks it, saps it of colour and shelves it somewhere at the back of his mind he can stymie the rising panic that accompanies it. It’s a trick he taught himself, a way to deal with the darkest thoughts, with the worst terror triggers. He can’t make them disappear, but he can stick them down the wrong end of his internal telescope, lean on the soft focus. In place of a smoldering, raged-up Marta and a discarded Pablo, he dips into the happy cupboard for a giant eagle, with wings like shields of feathered gold – much firmer ground in this sort of state.

Pablo is in the zone seven market. It’s not much of a market really, a handful of old people and kids with baskets selling fruit and tamales and what might be bicycle parts down one side of a street. He had told himself that Mariano may be down here and he could maybe tax him for an orange or a quetzal. Secretly he thought Marta could be here too. But neither of them are.

Three old indigenous women sit around a large pot wrapped in a blanket. The smell of the cinnamon steeping in the hot rice and milk prods Pablo’s hunger button, but he has no money and doesn’t fancy his chances at blagging these stony looking Quiche crows. He does, however, need to drink.

The man with the tortilla barrow has water in a jug, but Pablo still carries the remnants of the bruise he gave him last time him and Marta tried it on, so he doesn’t bother there. He walks along the row of fruit sellers until he sees a water bucket, with a bowl on top, and positions himself a couple of meters in front a girl with a basket of green, tired looking, tangerines. He squats and watches her. The wolf, el lobo, commanding, confident, waiting for the moment to snatch his prey… But he’s not the wolf, he is la ardilla, the squirrel, hanging out and trembling, hoping for some quiet at the lakeside, to sneak in and snaffle a drink.

In time, the girl becomes aware of the child watching her and, after ignoring him a while, gives him a nod and dips the bowl in the bucket. By the time she pulls it out Pablo’s hands are there to take it. He gulps it down. And a second, and a third. She tells him the fourth bowl is his last. And the next one. Pablo stops at six, his shirt front is wet and his mouth still dry, but he needed to add some water to whatever chemistry’s going on inside his body and, he hopes, in time he should notice some effect.

He hands back the bowl and the girl takes it.

“Vas,” she says, still without smiling and Pablo shuffles away. She watches him scuffle away hoping her brother is in school.

Pablo checks the dump, again, and walks the EJE1 from the flyover to the footbridge. There is no sign of Marta. He is not entirely sure whether he wants to find her or not. At least, he’d like to find her pleased to see him, but he’d rather not find her if she’s just going to tell him to get lost. At least unfound, he can fantasise about how she’s finding life without him.

He stands on the footbridge over the smoking, honking highway and imagines a giant eagle sweeping down out of the white of the sun and scooping him up with it’s beak and throwing him onto its back and away.

He walks up the coffin makers alley and crouches down opposite the small tienda on the corner. From here he can see the entrance to the dump and also down to the Diagonal. An old man, drunk in a doorway across the street, beckons Pablo over. He fumbles in his pocket as if for money and croaks something inaudible. Pablo leans in closer to hear. The man’s arm shoots out and grabs him by the scruff of his t-shirt and tugs him down, so the grit from the road bites into his cheek. But Pablo surprises himself. He digs the man hard in throat. Pablo panics yes, but he doesn’t wait for the cavalry, he knows she isn’t here. He buries his claws into the scrawny neck and the man lets out a cry. Pablo struggles free. The drunk tries to get up, calling out to a group of youths assembled around the tienda window. But they owe loyalty to neither street urchin nor bum and ignore them both.

In La Libertad, Pablo finds some children playing in the puddles by a standpipe and manages to switch off his dilemma for a little while to join in their game. They damn the water with their hands and feet before letting it sloosh their bottletop boats down the alley. They repeat the game over and over each time trying to see if they can make their boats go further than the last. Some lads come by buzzing with a story about a girl who was raped and killed and set on fire on the campo. They tell the youngsters that they’ve just come from looking at her still smoking body. Switch off… switch on.

Chapter 5.

It is dark in La Libertad and Pablo is out of ideas for finding Marta. He can feel his heart jabbing a castigating finger on the inside of his chest and at the small of his back his kidneys do their own little dance of complaint. His knees and elbows ache and he hasn’t eaten all day.

Maybe she really has gone. Pablo surprises himself with the thought. Last night he was too frightened to contemplate life without his grounding force, but today he thinks it straight out. Maybe it’s just him now. Him and the egg.

The Basura was closed by the time Pablo got back from the campo. The dead girl was not Marta, unless she had changed her shoes and her hand had grown half as much again in a day. She had not been at the rape house either, he had checked. And none of the children Pablo ran into had seen her, either at the tip or on the streets.

He is about to go back to where the egg is hidden when he decides to take a look down the western end of the zone, in the derelict buildings beneath the flyover. It’s gangland – for minors – the first port of call for the police when someone catches a bullet hip height. Pablo doesn’t really expect to find Marta there. He expects to find a bunch of glue-numbed pre-teen psychotics threatening to shoot each other. And he does.

The first face he sees is a familiar one – though this isn’t necessarily a blessing – it’s Burro, four and half feet of concentrated toe rag and one of the less likeable elements of the shoeshine brigade.

Burro is hanging about outside with some skeletal shadow in tow. But Burro is small fry in these catacombs. There’s plenty more violent – and imaginative with it – baby thugs here than him. A few of the shine boys try and tap Pablo up as he enters, but its clear he has less than even they do, so they let him slip inside.

A fire burns between two frameless windows in a room made crowded by about fifteen boys. Smoke snakes up the wall and whips out into the night as if pulled by a rope. A lad of eleven or twelve struts back and forth, ghosting in and out of the spasticated orange light of the fire. He has a gun in his hand. He looks like class factotum in hell’s own primary. A group of a dozen or so children sit and twitch and listen as much as their attention spans will allow.

Pistol boy – Pablo has seen him around his name, he thinks, is Abraham – is telling them how he killed a woman today. The class murmurs and he reads it as approval. He starts going into detail about how pretty she was and how pretty she isn’t now. He sounds like he’s making it up and Pablo hopes he is. Then another child, younger than Abraham by two or three years, gets up and produces his own pistol.

The older boy tells him to, “Put the toy away.” But the pint-size gunslinger won’t have it. Pablo reckons he’s about his own age. The revolver flails about as he tries to menace Abraham, the gun is too heavy for him to hold or control with the one hand. Pablo tries to figure out the best side of the room not to be on if and when the pistol goes off. They bicker – like anytown kids – with handguns. Big Pistol-boy eventually aces the challenger, by producing a fistful of quetzals he says he took from his victim. There is a dispute – another lad says the money is from a robbery he was also involved in this morning. Surprisingly, Abraham concedes the error, but the pretender has already resumed his place on the floor and in the pecking order.

Pablo works his way round the edge of the room. He has to step over conspiratorial groups of youths pulling on cigarettes and grumbling about having to move an inch to let him pass. Abraham is showing his pistol off to three teenagers sat in front of the fire, Pablo recognises two of them but doesn’t know their names. The third is a complete stranger.

“Seven in the magazine and one in the chamber. Enough for two full cop cars.” Abraham’s talk is as big as his pistol.

“You pull this out near any cops they’ll waste you before you’ve got the safety catch off,” the lad examining gun passes it back to Abraham. The other two laugh, so does Pablo.

“What the fuck are you laughing at?” says Abraham.

“Nada,” nothing, says Pablo, wishing he’d stuck to being invisible.

“Nothing. Nothing,” scolds Abraham pointing the gun at Pablo. “You got nothing, you are nothing… fucking laugh at me…”

“I do have something.”

Pablo hadn’t come here to attract attention, and definitely not to blurt out to these wing-nuts about the egg. Then again he’s not really sure why he’s here at all.

“I have something better than guns… or money…” he says, his voice wavers, putting the brush of a lie to his newfound fearlessness.

“Ha!” Abraham’s mocking tone alerts every smoke red eye in the room to the newcomer. All of a sudden the place seems a little less dark.

“You ain’t got shit Pablito!” He had not noticed Burro who has come inside and is now standing across from him on the other side of the fire.

“I have something. I found it… on the basura.”

“It’s a bicycle tyre.” A laugh goes up.

“A chicken wing.”

“A broken shoe.” A bigger laugh. Pablo bristles.

“I have…”

“You have an arse. Sit on it!” Pistol boy is missing his spotlight.

Jeering laughter washes around the walls of the room like a wave in a shoreline cave. But Pablo, needled by the mockery, ploughs on.

“I have something that will make everything right.” He barely recognises his own voice, raised an octave from its already squeaky baseline and doubled in delivery speed. The kids fall about, though not the teenage stranger.

An idiotic looking stoner youth hunched next to Pablo pushes him and tells him to sit down. But Pablo has no intention of sitting. He’s never had the urge to speak above the crowd before, he’s never had anything to say before. He’s never had an argument, or held a strong enough opinion to get involved in anyone else’s. But now he has a corner to defend.

“Leave him alone!” Marta stands in the doorway. Her shout cuts the laughter out of the smoke. But only for a moment. The hiccup of silence is broken by more insults, this time for Marta.

“Mamacita. You come to save your baby?”

Marta makes no effort to hide her disgust of the banda kids. She will not be intimidated, at least she won’t show it, not even when Pistol Boy sidles up so close she can feel his breath on her cheek. She decides not to punch him unless he actually touches her.

“Let’s go Pablo.” She beckons to him, fuming in his corner. He hesitates. He has pined all day for her to come, but now she is here he doesn’t want her – fighting his battle, making his decisions. Now he has the egg, he doesn’t need her. Does he? Marta stands defiant. The gang kids don’t appear to frighten her. Seeing her facing off these pricks tugs the rug out from beneath him. Pablo’s confidence evaporates. He buckles. He crosses the room to where she is. No one tries to stop him. They leave under a barrage of insults and name calling.

Marta is apologetic.

‘I’ve been looking all over for you. I was worried. I thought maybe Golden Boots had got you.”

“I thought you were the one who left me?”

“I wasn’t well Pablo. Some women took me to their home. They have this… house. I slept there last night. It belongs to a woman called Esperanza. She can help us.”

Us? Yesterday she cut him loose and now she was talking about ‘us’. Yesterday? It seems like a long time ago to Pablo. His body hurts. Pagamente, it’s a greedy bed fellow, it doesn’t just up and leave with the eastern rising. It likes to stick around the next day, longer if you let it – keep you sharpened, every rattling cell.

Pablo is short of breath, he is hungry and he hurts. He needs to sleep. He needs to eat. They walk back along the EJE and cut up by the east wall of the basura. They cross into zone three but walk on past La Libertad and into the houses on the slopes above. Marta leads. Pablo follows. It was always this way, but tonight Pablo is less certain this is the right path to follow.

They turn right, left, right again. He has not been in this area before. The odd car lurches past, bouncing through the gaping potholes where the road has fallen into the subsiding soil beneath. They quicken their pace when the cars drive by too slowly, or have no lights on.

The house is warm. And the bed is soft and forgiving. Washed and fed, Pablo lies with his head on Marta’s lap. She strokes his face. Her clothes have been washed. He had not noticed earlier in the confusion of the catacombs or in the darkness of the street, but she is wearing a necklace. It is a small piece of stone with a figure carved into it. It is clumsily done, but Pablo can make out a woman and maybe a snake. Pablo recognises the character as one of Rosa’s, it is the Moon Goddess Ix Chel. Marta says it is a present from Esperanza.

“They call her Senora Arco Iris, Lady Rainbow,” explains Marta – repeating the explanation she was given. “She carries a great big jug of water and when she tips it out, rainstorms fall from the sky. She controls all the waters of the world Pablo. And she looks after women having babies, and weavers too.”

“My mother is a weaver,” says Pablo. But for once he’s not entirely sure about this. Marta knows different.

Pablo fingers the trinket and Marta strokes the boy’s hair. She smells different, she smells of coconuts. Pablo breathes it in. It chases the smell of the glue away. She tells him everything is going to be okay. She tells him she will look after him.

They are sliding back into their allotted roles. But something is different. Marta is less convincing. Pablo is less convinced.

Finally Pablo says: “I have a way to take us both away from here.” Marta makes slow circles on his forehead with her thumb. “I found an egg. On the dump.”

“An egg?”

“Yes, an eagle’s egg. It was in a nest but the mother bird did not come back for it. I waited to make sure. I took it. I put it in the pouch you made for me. It is warm, I felt it move.”

“Puedo verlo?” Can I see it?

“It is hidden. I wrapped it up to keep it warm.”

“Where?”

Pablo hesitates. Marta has been his sounding board, his confidante, his middleman, his bridge to the world. But, now, for some reason he is reluctant to reveal his hiding place to her. He knows the old woman is near. But it’s not just that.

Marta can see the confusion on Pablo’s face. Maybe he can’t think of somewhere convincing to say. She doubts the egg exists, but that doesn’t seem important.

“So how will this egg take us away from here?” she asks.

“The eagle will take us away. It will make sure no one ever hurts you or me ever again. We will look after it and when it is grown it will put us on his back and fly home. Back to my mother’s house.” He is trying to talk quietly, out of Esperanza’s earshot, but his desire to make Marta believe him, understand him, appreciate him for achieving something without her is reflected in the rising panic and volume of his voice.

She smiles at him. She has no desire to break the spell. Marta remembers Pablo’s mother. A junk-sunk skinny rake in a short red skirt people called Tia Juanita. She had worked the EJE1, turning tricks for fat cabbies and clean-fingered business men on the way home to their wives in Antigua. The baby didn’t help matters. It just got in the way. The old woman who lived in the adjoining shack would look after it, feed it, tell it stories, when the mother went out working and left it on its own.